Share this

An Update On The Debate On Privacy For A Digital Euro

by Ludovica Maria Chiapuzzi, Meglena Grueva on Mar 10, 2023 6:58:15 AM

As the evolution of the internet and the digitalisation process go forward, the awareness of the value of privacy[1], along with the necessity to guarantee and protect it, increases.According to the current European legislation, privacy is a fundamental right, enshrined in Article 8 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights[2]. The legal framework is completed by the Data protection package adopted in May 2016, which is composed of the General Data Protection Regulation[3] (GDPR) and the Data Protection Law Enforcement Directive[4]. The first, legislation, aims to protect natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data as well as the free movement of such data, while the second regulates the processing of personal data connected to criminal offences or the execution of criminal penalties and the free movement of such data.

One should keep in mind that a shift to digital payments, and the eventual adoption of a public digital currency, will inevitably lead to less privacy. From this perspective, payments in cash offer the most privacy, it is not possible to only rely on this scenario anymore. In the Report on a digital euro, privacy was highlighted as a key concern of future users. This has been further confirmed by responses collected during the consultation phase, in which privacy came up as one of the most important and wanted features for the digital euro. In particular, users desire the possibility to make both online and offline transactions (“pay anywhere”) while maintaining a degree of control over their personal and transactional data[5]. As underlined by Fabio Panetta,[6] such a request must not be a surprise. At this point, it is a well-known fact that private companies processing digital payments[7], monetise more and more on personal data. While the ECB has no interest in making a profit from users’ data, EU citizens tend to doubt statements from institutions, and prefer a preventive approach which guarantees the safe usage of their personal information.

In one of his papers, professor Donato Masciandaro[8], distinguished between a physiological and pathological need for privacy in people. The physiological need stems from the desire for personal information to not be disclosed freely, and is a legitimate interest protected by law (within certain limits). Alternatively, the pathological need conceals illicit conduct and exploits the right to privacy to cover the said conduct. An example can be offered by the omnipresent crime of money laundering –worsened by the widespread of crypto-assets – which consists of concealing or disguising the origins of illegally obtained proceeds so that they appear to have originated from legitimate sources[9], a process which is easier to complete if its author manages to maintain his/her identity unknown.

These considerations are useful for understanding one of the most sensitive issues related to privacy. It is evident how, from a certain point of view, money and everything that is connected to its use can be seen as a source of personal information. Therefore the protection of private data is at the centre of attention within the ECB project. Respecting the privacy of transaction data is important for ensuring the data’s security and fair pricing and avoiding data exploitation[10].

However, there are other essential necessities to be considered and cannot be fully sacrificed in favour of privacy requests. It is fundamental to strike the right balance between the protection of data security, efficiency and compliance with applicable regulations: if, on the one hand, the respect for users’ privacy is felt like something indispensable, on the other one, the necessity of preventing illicit activities, namely money laundering and terrorist financing, has been generally recognized. This inevitably requires a form of identification and tracking by competent authorities, who may need to know what amount of money is transferred from one subject to another. This is one of the most debated trade-offs within the digital euro project. Starting from the current legislation, the ECB must comply with both the GDPR and the anti-money laundering and anti-terror financing regulations[11]. Privacy should be assessed in the context of the EU policy objectives (AML/CFT), since it cannot come at the expense of security.

Even before preliminary work on a digital euro began, the ECB conducted a few studies on privacy-enhancing techniques (PETs) in CBDCs. The first[12], in 2019, resulted in a proof of concept (PoC)[13] that allowed to limit sharing of the information of users who made low-risk and low-value payments and, while monitoring illicit activities[14]; a year after, in 2020, a conjunct work[15] made by experts from the ECB and the Bank of Japan lead to further exploration of this topic. These two projects constitute a starting point to satisfy the demand of privacy for a digital euro which emerged from the consultation phase.

Considering the necessity to protect different types of data – user’s identity, data on individual payments like the amount of payment, metadata related to a transaction like the IP address of the used device – and starting from those bases, different streams of work have been identified.

First, it is necessary to minimise the amount of personal information that will inevitably be stored in the infrastructure of a future digital euro – either in a ledger, or a centralised one. Among the options considered is the segregation of data. Data shall be aggregated on a “need to know” basis, and no participant will know that a certain transaction is taking place between any two users; however, if the necessity to investigate illicit activities emerges, competent authorities will be able to request and obtain such information.

Secondly, payment operators shall not have access to transaction data, inferring private information[16].

Third, it is important to understand the implications of off-ledger payment channel networks in which the payment details will only be known to the payer and the payee, hence hidden from any other third party (including the central bank).

Finally, the ways to shape different elements of a blockchain prototype – such as ledger, wallets, and identity services – in order to grant different levels of privacy are being tested. Moreover, the possibility for local storage is considered.

For example, using a bearer instrument to pay would make bearer solutions very similar to cash, which is distributed by intermediaries and then transacted between users in line with their sole responsibilities. In this case, the payer and the payee would be responsible for verifying any transfer of value between them without the involvement of a third party. For each of these streams, an analysis of privacy is being conducted with a constant, specific focus on anti-money laundering requirements.

Finding the proper balance between a high standard of privacy in the use of digital euro and previous EU policy objectives, inevitably excludes full anonymity to users, as this impedes any control over the amount of digital euro in circulation, hence prevention of money laundering and other illicit activities.

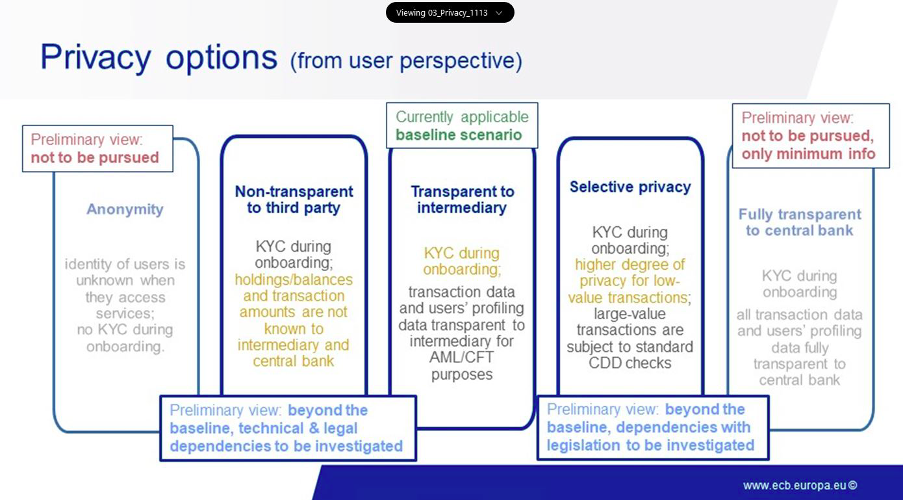

As of mid-2022, three different privacy options for a digital euro[17] have been concretely prospected.

- a) Transparency to intermediaries

In this scenario, a digital euro would provide people with a level of privacy equal to that of private digital solutions: checks during onboarding would be done and competent intermediaries would have constant access to personal and transaction data in order to ensure compliance with AML/CFT requirements.

- b) Selective privacy: privacy for low-value payments

Such a scenario would require customer checks during onboarding, but it would then guarantee a diversification of privacy treatment based upon the value and the risks connected to payments and economic transactions. For low-value and low-risk payments, a higher degree of privacy would be provided, thus leading to simplified checks (a hypothesis could be a specific wallet with lower requirements during onboarding); while higher-value transactions would remain subject to standard controls, as prospected in the first scenario.

- c) Privacy under offline functionality

Customer checks during onboarding would be an inevitable function, but such a scenario – which clearly is the most convenient one for users – would provide fully private offline transactions and balances, non-transparent to intermediary or central bank. Then, in order to contain risks of illicit activities, full privacy could be granted only for close proximity payments that are low-value and low-risk.

Of these possibilities, the first one is the baseline scenario, being subject to current legislation, hence it is already applicable. The other two options – which have the ambition to provide a higher degree of privacy than any other existing payment solutions – require further investigation from the ECB, together with co-legislators, for integrating such features in the regulatory framework. The Eurosystem already considers the possibility to go beyond the baseline scenario: such openness shall lead to a reform related to the current Data protection package – and will be a part of a broader legislative reform triggered by the realisation of the digital euro project.

Below, a complete scheme of all the options that discussed so far is available.

To conclude, if the European legislator accorded to privacy the status of fundamental right, it gives it a highly protected value, and every issue regarding it must be fully considered.

However, a last consideration about the concerns related to a digital euro and its respect of privacy could be made, even if there is a risk to express a very unpopular opinion. In everyday life, sharing and traffic of data is very intense and it is barely possible to escape. It is almost inevitable for an individual’s data to become an object of lucre, being sold to private companies which may disrespect the principles of privacy; the rapid and unstoppable evolution of data sharing requires the search for a way to stem the problem, and not to remove it. In this context, the high attention to privacy within the digital euro project is justified and should be read as a welcomed consciousness.

Still, in the face of a phenomenon so vast and hard to handle, the insisting interest in privacy issues related to a CBDC might seem specious and betray an enrooted, pervasive distrust of citizens towards the Institutions, which expresses itself in various forms of unhealthy individualism. Such distrust inevitably leads to a diffident and polemic approach to any proposal offered at a public and institutional level, inevitably slowing down any innovation process.

References

[1] Broadly speaking, privacy is the “right to be let alone”. In this case, it consists of “information privacy”, the right to have some control over how your personal information is collected and used.

[2] The Charter is a legally binding document, declared in Nice in 2000 and later put into force in December 2009, along with the Treaty of Lisbon, to which has been equalised. Its purpose is to promote human rights within the territory of the EU. Article 8 (Protection of personal data): 1. Everyone has the right to the protection of personal data concerning him or her. 2. Such data must be processed fairly for specified purposes and on the basis of the consent of the person concerned or some other legitimate basis laid down by law. Everyone has the right of access to data which has been collected concerning him or her, and the right to have it rectified. 3. Compliance with these rules shall be subject to control by an independent authority.

[3] See Regulation (EU) 2016/679.

[4] See Directive (EU) 2016/680.

[5] Personal data are understood as any information that relates to an individual who can be identified (name, physical and email addresses and location information); while transaction data include any information related to a specific payment, which includes payer’s wallet or account number, transaction counterparty, transaction amount, date, time and location of the transaction, and also information about goods and services purchased, along with billing or shipping address.

[6] See Introductory remarks by Fabio Panetta, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the ECON Committee of the European Parliament, Frankfurt am Main, 14 April 2021.

[7] It is a phenomenon related to anything that concerns the digital sector. The so-called GAFA (Google, Amazon, Facebook e Apple), the big four of tech world, are known for having developed technologies to exploit their users’ data for lucrative scope. In fact, the more they collect data they more they can target advertisements or their product and services. Source: Sofrecom.com.

[8] Donato Masciandaro is an economist and Full Professor of Political Economy at Bocconi University (Milan, Italy). See Masciandaro D., Ci sarà l’euro digitale? Sì, e sarà doppio, in Economia & Mercati, 8 Novembre 2020.

[9] Moreover, this crime is usually committed with other serious offences, such as drug trafficking, robbery or extortion. Source: Interpol.int

[10] Data exploitation refers to any usage of people’s private data which is not expressly considered and allowed by law. Due to the evolution and the widespread use of the Internet, the traffic of personal data across different platforms and their subsequent storage is almost inevitable and the exploitation phenomenon is becoming more and more frequent, also due to the substantial lack of limit to the reuse of single data.

[11] See Directive (EU) 2015/849, amended by Directive (EU) 2018/843, on preventing the use of the financial system from money laundering or terrorist financing and Regulation (EU) 2015/847 on information on the payer accompanying transfers of funds. All these instruments take in account the 2012 recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

[12] See ECB, Exploring anonymity in central bank digital currencies, In Focus, No 4, December 2019.

[13] Also known as proof of principle, a PoC is an exercise in which work is focused on determining whether an idea can be turned into a reality. It is not intended to explore market demand for the idea nor to determine the best production process, its scope is to determine the feasibility of the idea or to verify that the idea will function as envisioned. Source: TechTarget.

[14] “In the use case analysed, any user’s intermediary would only know that a payment of a small amount has been made or received, but without knowing the identity of the counterparty involved in the transaction. It would therefore be impossible for any intermediary to know the purpose of a low- value payment made or received. The PoC set a maximum overall amount of private small payments each user can make in a given time period. This would be established in line with the regulatory framework to stop large payments being split into several small payments to circumvent the regulation. The solution was based on assigning a number of time- limited “digital vouchers” to each user, who could use them to privately transfer central bank digital currency. The impossibility of tracking past payment activity would preserve the privacy of users” from The Eurosystem’s analysis of privacy-enhancing techniques in central bank digital currencies.

[15] See ECB and Bank of Japan, Balancing confidentiality and auditability in a distributed ledger environment, Project Stella, February 2020.

[16] To this purpose, experimentations on the use of one-off cryptographic public keys and end-to- end encryption are being carried.

[17] See Eurogroup, Digital euro Privacy options, May 2022.

About the authors

Ludovica Maria Chiapuzzi is a Law graduate and a young professional who operates within the environmental finance. In fall 2022, she graduated from University o Milan with a dissertation on the realisation of the ECB project on a digital euro, from a juridical and economic perspective. She cultivates her interest in CBDCs and private digital money through active participation in the Digital Euro Association (DEA), for which she is currently writing a series of educational articles.

Meglena Grueva is a Senior Manager within Mazars financial services practice in Germany. She has significant knowledge and experience in prudential regulation of the EU banking sector. In the past years, Meglena has developed her expertise in digital assets and blockchain regulation and is presently pursuing a Master of Science in this field at Frankfurt School of Finance and Management. Meglena is part of Mazars Global Financial Services Regulatory Hub, which deals with banking regulatory issues. She follows regulatory developments in the EU, and her present focus is on the Digital finance package for Europe. Prior to joining Mazars, she worked at the European Central Bank, was in a tax advisory firm in New York, USA, and was an investment analyst at a private family office practice in Chicago, where she covered global capital markets.

Share this

- CBDC (44)

- Events (27)

- Partnership (27)

- Stablecoins (25)

- Digital euro (24)

- Quarterly Insights (8)

- ECB (7)

- Privacy (4)

- Thesis Awards (4)

- Article series (3)

- Central bank digital currencies (3)

- Crypto (3)

- Jobs (3)

- Law, regulation & policy (3)

- Tokenized Deposits (3)

- digital yuan (3)

- Academics (2)

- DEC23 (2)

- DEC25 (2)

- Digital Money (2)

- Members Assembly (2)

- MiCA (2)

- Public Hearing (2)

- Regulation (2)

- Sand Dollar (2)

- e-CNY (2)

- monetarypolicy (2)

- Adoption (1)

- Ai (1)

- Blockchain (1)

- Central Banking (1)

- Cross-Border (1)

- DEC24 (1)

- Diem (1)

- Digital Euro Association (1)

- Digital Pound (1)

- Digital Pound Foundation (1)

- Education (1)

- Eurocoin (1)

- Facebook Pay (1)

- FinTech (1)

- Geopolitics (1)

- Novi (1)

- Offline (1)

- Petition (1)

- Project Hamilton (1)

- Public Affairs (1)

- Quantum (1)

- Ripple (1)

- Technology & IT (1)

- USA (1)

- investors (1)

- June 2025 (1)

- May 2025 (4)

- April 2025 (5)

- January 2025 (1)

- December 2024 (3)

- November 2024 (3)

- October 2024 (4)

- September 2024 (2)

- August 2024 (3)

- July 2024 (6)

- June 2024 (1)

- May 2024 (4)

- April 2024 (4)

- March 2024 (4)

- February 2024 (4)

- January 2024 (2)

- December 2023 (3)

- November 2023 (2)

- October 2023 (3)

- September 2023 (5)

- August 2023 (5)

- July 2023 (9)

- June 2023 (5)

- May 2023 (3)

- April 2023 (2)

- March 2023 (7)

- February 2023 (3)

- January 2023 (3)

- November 2022 (2)

- October 2022 (4)

- September 2022 (8)

- August 2022 (11)

- July 2022 (4)

- June 2022 (5)

- May 2022 (3)

- April 2022 (6)

- March 2022 (8)

- February 2022 (6)

- January 2022 (1)

- December 2021 (1)

- November 2021 (1)

- October 2021 (1)

No Comments Yet

Let us know what you think